Early career researchers at the UN Ocean Conference

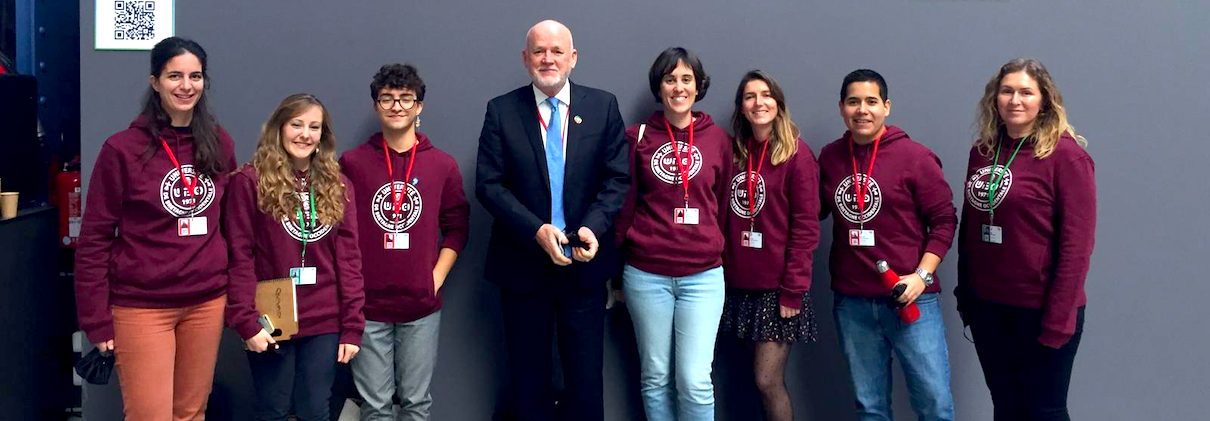

A part of the early career researchers team with the Secretary-General’s Special Envoy for the Ocean, Peter Thomson

Call for action One Ocean Summit University

The University of Brest (UBO) mobilized its partner networks to initiate a joint contribution of early career researchers for the One Ocean Summit in Brest (February 2022).

A group of more than sixty PhD students and postdoctoral researchers from various nationalities and disciplines have been working together to put forward a common view of the challenges and opportunities for research and research training in marine sciences. Their common goal is to present this call for action at the United Nations Conference on the Ocean, to be held in Lisbon from 27 June to 1 July 2022.

I- Secure an equitable and integrated ocean governance

I.1. Reinforce integrated governance horizontally (between all stakeholders) and vertically (between the local, regional and international levels)

Ocean governance must integrate fairly all relevant stakeholders and sectors, such as NGOs, government agencies, international institutions and communities. It must be well-designed to ensure effective communication and action between and within the local, regional and international levels, with planning integrating a long-term vision and concrete short-term actions.

- Align tools, treaties and institutions to secure coherence in ocean governance and management;

- Encourage polycentric governance to ensure the participation of civil society, public and private stakeholders;

- Apply participatory modeling and the use of workshops and dialogues among stakeholders to boost interaction and foster integrated approaches at different levels.

I.2. Integrate research into ocean governance by strengthening the science-policy-society interface

A strong science-policy-society interface is needed to support evidence-based approaches to ocean governance and thus achieve the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 14 and its targets.

- Create an International Panel on Ocean Change to strengthen interaction between scientists and decision-makers and establish evidence-based policy action plans based on the precautionary principle. Ensure that scientific evidence is openly available and up-to-date for decision-makers and society;

- Define what the good environmental status of the ocean should be, based on scientific knowledge;

- Encourage the use of social sciences to raise awareness of ocean policies and accompany their social acceptability.

I.3. Implement transboundary programs to overcome fragmented ocean governance and foster collaboration at the ocean-basin level

Collaboration between countries sharing the same ocean basins is key to ensure effective governance and develop a more integrated view of maritime issues. At the ocean-basin level, joint efforts must be implemented through transboundary programs.

- Enhance capacity building and technical support between countries sharing the same ocean basin. This should include a common funding tool to boost measures against pollution and for climate change adaptation, particularly in small island developing States and the least developed countries;

- Create a shared space for networking and communicating between national and regional agencies at the ocean-basin level;

- Pool transboundary monitoring resources to ensure compliance with maritime laws;

- Enable public involvement and participation of all stakeholders, including youth and local communities, in maritime and ocean policies at the ocean-basin level.

II- Improve ocean management to ensure resilience

II.1. Increase the protection of marine ecosystems and restore degraded ones

Protecting and restoring oceanic ecosystems is critical for preserving biodiversity, reducing climate change impacts and ensuring the provision of ecosystem services. Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are a key tool to protect and restore the ocean but should not be the only one considered. A major challenge to ocean management is to both improve approaches to biodiversity conservation and implement effective restoration strategies.

- Protect at least 30% of the ocean by 2030 with a high level of protection and sustainably manage the remaining 70% to ensure resilient marine ecosystems;

- Define protection according to internationally-agreed, evidence-based criteria (e.g. MPA guide);

- Increase the number, size and protection levels of MPAS: only high levels of protection will enable MPAs to be effective;

- Allocate sufficient funds for effective governance and management of MPAs (including for coercive measures and rewarding best practices) to ensure the achievement of their conservation goals and objectives, while considering their respective socio-environmental contexts;

- Secure the conservation and restoration of all ecosystem types (including corridors) in all ocean basins, and not only in remote areas;

- In international waters, use an ambitious High Seas Treaty (BBNJ) to allow the creation of large-scale and mobile MPAs;

- In polar regions, which are particularly under threat, i) agree on an international definition of the state of the poles, based on the pre-industrial era in terms of physical boundaries and biodiversity status; ii) speed up MPA designation: in the Southern Ocean, implement the MPAs envisioned by the Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR); in the Arctic, create MPAs and ensure that legislation applies to all states equally; iii) restrict exploitation such as fishing, seabed mining and tourism.

II.2. Design adaptive and integrated marine spatial plans to sustainably manage the ocean

In the context of increasingly busy ocean spaces (offshore aquaculture, increase in shipping and trade, marine energy production, increasing coastal populations, mass tourism), integrated spatial management is crucial.

- Implement adaptive marine spatial planning using ecosystem-based approaches, allowing dynamic management tools (e.g. mobile MPAs), integrating the land-sea interface (e.g. to address land-based pollution), adapting to climate-related impacts and considering all human-environment interactions in a holistic way;

- Promote synergies between activities and territories such as integrating marine renewable energy development with fishery activities while considering the acceptance of coastal communities;

- Secure transparent integrated impact assessments (considering cumulative impacts) and monitoring strategies;

- Allocate sufficient funding to accelerate the transition towards the use of non-destructive practices;

- Establish tourist carrying capacities in sensitive areas (e.g. MPAs) and manage holistically the overall flow of tourists in coastal areas;

- Implement eco-friendly practices for boating activities (including leisure boats and cruise ships) such as ecological moorings, speed limits (i.e. no-noise zones) and limitations on cruise numbers;

- Safeguard cultural heritage and recreational uses within the expanding blue economy.

III. Guarantee a sustainable and fair Blue Economy

III.1. Ensure the resilience and equitable sharing of ecosystem services

The ocean is facing multiple anthropogenic pressures threatening the sustainability of its use as a source of food and health for current and future generations. It is therefore necessary not to over-exploit marine resources and endanger their survival for the next generations.

- Develop ecosystem approaches to fishery management and integrated multi-trophic aquaculture systems to secure food provisioning;

- Promote the recycling of seafood by-products and the consumption of new food resources such as algae to release pressure on heavily exploited stocks and ensure access to products with high nutritional values;

- Define and publicize eco-scores for all seafood products based on their environmental impacts.

III.2. Make the protection of the environment a systematic criterion for awarding funds in the maritime sector

International and national legislations must be aligned with ocean protection. Forthcoming projects supported by public and private funds must satisfy precisely defined environmental and social criteria at all levels (international, regional, national and subnational).

- Particular attention must be paid to ensure that social equity and ecological issues are not ignored in the face of economic priorities and to secure fair and equitable sharing of the benefits of the exploitation of marine resources (the ocean as a common good);

- Redirect financial flows from harmful subsidies to incentives to protect marine ecosystems;

- Establish financial compensation for damage: enforce the “you harm, you pay” principle by local stakeholders, sanction harmful practices through green taxes whose receipts are re-injected into restoration activities;

- Make corporate responsibility legally binding to prevent the misuse of ocean resources;

- Scale up blue investments, with consideration of both biodiversity and climate change, and ensure sufficient funding for assessment, management and monitoring;

- Use innovative finance tools (e.g. public-private partnerships following sustainability guidelines, carbon markets);

- Strengthen the capacity of ocean managers and finance partners so they can work together.

III.3. Reshape ocean tourism

Marine tourism is an important part of the blue economy and changes must be made to ensure that it encourages more environmentally-friendly activities.

- Promote the sustainable and responsible management of marinas with a common environmental policy and through an eco-label;

- Implement local measures to tackle marine pollution from tourism;

- Raise awareness of ocean protection and marine life welfare, including its exploitation for entertainment, among tourists;

- Support organizations that offer ecotourism training;

- Increase awareness of tourists by encouraging marine resorts to offer sustainable activities (e.g. promoting beach cleanups as a tourist activity) and assigning a travel score reflecting their comprehensive carbon footprint.

IV- Strengthen ocean science and literacy for a sustainable ocean future

IV.1. Support transdisciplinary and holistic research and embrace a collaborative, diverse and open science

In order to achieve the targets of SDG 14, it is imperative to increase scientific knowledge and the capacity for both fundamental and applied research. The generation and sharing of local knowledge by local and indigenous populations, NGOs and other marine stakeholders is also paramount to provide solutions to local and global issues.

- Encourage transdisciplinarity in ocean sciences and integrate evidence from different fields of ocean sciences and marine knowledge holders;

- Increase funding for marine sciences and distribute financial resources equitably across disciplines and geographies for the development of integrated solutions in favor of ocean protection and societal adaptation;

- Ensure sustainable research practices which respect the ocean (eco-friendly marine vessels, prohibition of single-use plastic, carbon budgeting);

- Facilitate the mobility and exchanges of scientists, including Early Career Researchers and local marine actors;

- Invest in new generations of marine researchers, including improving the quality of life of Ph.D. students and post-doctoral researchers;

- Increase the number of available permanent positions in research to sustain long-term research projects, for a better understanding of the ocean in a changing world;

- Better manage, integrate, centralize and exploit ocean data that have been collected at different levels and times to improve understanding of the ocean in response to changes;

- Develop new data management and analysis tools to facilitate ocean monitoring and surveillance.

IV.2. Make the ocean an integral part of an environmental education program

Educational structures are a powerful tool to promote ocean literacy and raise awareness of anthropogenic pressures and threats. To ensure the legacy of SDG 14, an environmental curriculum including the ocean should be implemented in schools to enhance children’s connection to the marine environment.

- Create an environmental curriculum including the ocean in national educational programs, in line with local socio-environmental contexts, and support its implementation across countries, including small island developing States and the least developed countries:

- Enhance children’s familiarity of the marine environment by setting up projects related to the ocean for each level, structured around science-based interactive and in-person experiences, to build connections with the ocean and appreciate the services it provides;

- Transform societies into sustainable socio-ecosystems to preserve resilient ecosystem services and cultural heritage for all generations.

Photo credit

Eva Ternon / UPMC

Contact

Romain Le Moal / UBO